Written and researched by Chris Bell

Copyright, Chris Bell, 2016

First published in The Telamon, the Magazine of The Friends of Kensal Green Cemetery.

[Thomas Milnes carved the lions, War, Peace, Determination and Vigilance which adorn Victoria Road, Saltaire.]

"Determination"

the lion. One of four on Victoria Road, Saltaire.

Chris Bell writes: It’s a pity that my wife isn’t a celebrity as her family history has all of the must-have ingredients for Who do you think you are! I’ve always been slightly envious of her ancestor who fought in the Crimea and then in India, another who fought in the Peninsular War and maybe, just maybe , at Waterloo, to say nothing of the one who was the leader of a notorious gang and who was transported to Van Diemen’s Land aboard The Lotus in 1832. But then I discovered Thomas Milnes, sculptor, buried in Kensal Green cemetery …

My Milnes connection comes through my grandfather’s mother Ellen Sarah Milnes, who was born in Snettisham, Norfolk in 1871. My grandfather, Fred Wagstaffe, was an avid family historian who wrote monographs on every branch of the family. His notes on the Milnes family begin with the words “I know so little about my mother’s family that I doubt whether it is worth recording”, followed by four pages of closely written typescript!

Grandad certainly knew that his grandfather was one John James Milnes and that he was a stonemason with something of a temper! The family had moved to Tottenham by 1891 but we don’t know what happened to John James himself after that. Three of his sons followed him into the same trade, all living in the same street in South Harrow, Middlesex before WWI. That was the starting point for this part of our family history research in 1983. Back in the day we didn’t have the advantage of the Internet or even a computer but Norwich Record Office were ever helpful and it wasn’t too long before we found, courtesy of the 1851 census, that John’s father was 55-year old Charles Milnes, a stonemason resident at Stonemasons’ Yard, Norwich and employing three men.

Charles wasn’t a local man. His birthplace was given as Tickhill in Yorkshire, a small town near Doncaster. Next stop the parish registers of St. Mary, Tickhill in Doncaster archives, from which a friend painstakingly extracted all of the Milnes entries in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. A Charles Milnes was baptised on 22 Nov 1795, one of no less than 14 children of John and Mary Milnes baptised between 1793 and 1818. There is a marriage of a John Milnes and Mary Hopkinson on 14 Jun 1792 at Blyth, Notts, less than five miles to the south of Tickhill, which fits very nicely.

Some websites will tell you that Thomas was born in 1813. He wasn’t! His age is stated in no less than nine records, which, discounting the 1841 census with its rounded ages, still leaves a year of birth anywhere between 1809 and 1813. The latter date comes from having given his age as 28 when he entered the Royal Academy Schools in 1841.

Thomas’ gravestone at Kensal Green gives his date of birth, presumably supplied by his widow, as 21 Dec 1810. All of the censuses from 1851-81 show his birthplace as Tickhill, Yorkshire and there is indeed a Thomas Milnes, son of John and Mary Milnes baptised on 26 Jan 1810. Assuming that he did know when his birthday was, this strongly suggests that he was actually born in December 1809, but I guess we’ll have to settle for ‘c1810’ because we can’t prove it.

Unlike on Who do you think you are there was no family legend that we were related to Thomas Milnes but the evidence stacks up that he was a 4-greats uncle to me, so I am very happy to write this article about a man who deserves to be better known.

We know nothing of Thomas’ early life, but after his death in 1888 a letter, written by ‘a correspondent’ presumably as a sort of obituary, was published in The Athenaeum [1]. I was able to obtain the full text from Princeton University in New Jersey but I do not believe that all of its contents can be taken at face value. It states that Thomas’ father was a cousin of R. Monkton Milnes (Lord Houghton) and had ‘dissipated his means and neglected his son’s schooling so that he remained illiterate’. It claims that Thomas was encouraged in his art by his aunt Lady Galway and other relatives.

The ancestry of ‘our’ Thomas Milnes is known back to his grandparents Charles Milnes and Elizabeth Hopkinson, who came to Tickhill in 1775 and baptised the last six of their ten children there. The baptism entry for their son Thomas Milnes (an uncle of our Thomas) in 1779 describes Charles as a ‘stonecutter’.

The ancestry of Robert Monkton Milnes is known back at least as far as his great great grandparents Richard Milnes (b1696) and Bridget Pemberton [2].

Baines’ Yorkshire gazetteer of 1823 [3] describes our Thomas’ father John Milnes as a stonemason, as does his will of 1829. Genealogical research has so far revealed no discernible link between him and Monkton Milnes in the way that is stated in the letter in the Athenaeum, neither is there anything which suggests that John was ever anything other than a small town stonemason.

So was the Richard Monkton Milnes connection a yarn spun by Thomas himself in an attempt to improve his social standing? His second and third marriages might support this view.

Thomas had arrived in London by 1836 and married Sarah Betsy Harrad in the Parish of St. Mary-le-Bone on 19 May of that year. Intriguingly both the 1841 and 1851 censuses show him living with his wife ‘Emma’ Milnes, one year older than him, with no birthplace shown for her in 1851. Sarah, however, reappeared in 1861, now six years older than him! She died of apoplexy on 1 Apr 1867.

Thomas wasted no time at all in finding a second wife, marrying Frances Eidsforth on 16 Jul 1867 at St. George, Bloomsbury. Her father Anthony Eidsforth was a notable citizen of Lancaster. She died in late 1875 and on 1 Jun 1876 Thomas was married for a third and final time, to Jessie Anne Fletcher at St. Mark, Regents Park. Her father, John Fletcher of Shifnal in Shropshire, was a surgeon [4] and her brother, Thomas Bell Elcock Fletcher, was an eminent physician [5]. Jesse survived her husband by nearly 25 years and appears to have been something of a feminist . Probate of her will, proved in London in 1912 [6], indicates an estate worth nearly £4000. She left legacies to her nieces but not to her nephews and stated that ‘all the said legacies given to married women shall be for their respective separate use’ [7].

No children of any of these marriages show up on census which suggests that he had no direct descendants.

The biographical dictionary of sculptors in Britain [8] currently lists no less than 45 works by Thomas Milnes but, perhaps surprisingly, 27 of these are untraced. It has been a labour of love – and great fun – to try to visit and photograph all of the surviving works but as our research progresses the goalposts keep moving and we still don’t quite have a full set!

Milnes entered the Royal Academy schools on 21 April 1841 on the recommendation of Edward Hodges Baily, RA, best known for his statue of Horatio Lord Nelson atop Nelson’s column in Trafalgar Square. For the best part of the next 25 years Milnes advertised his work in exhibitions at the Royal Academy [9] and elsewhere and it is most of these works which are untraced.

During his lifetime Milnes had studios at a number of prestigious London addresses, including 3 Judd Place East, Bloomsbury (1845-57) [9], [10], 40 Euston Road (1861) [11] and 4 Euston Square (1867) [12].

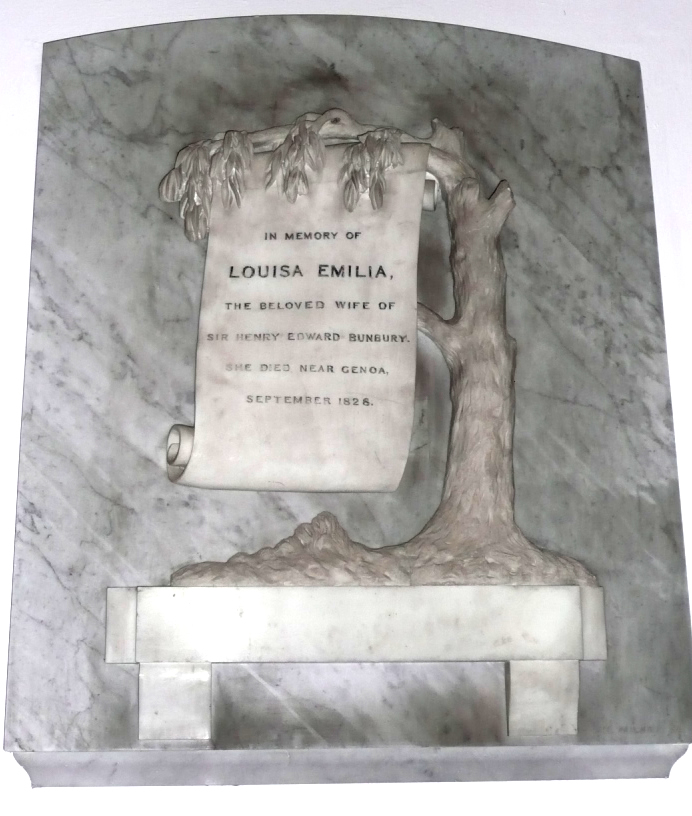

Although Milnes completed three full size statues, his skills as a sculptor are perhaps better displayed in the fine detail of the six known wall-mounted funerary monuments in churches. These range from the medallion portraits of John Raymond Raymond Barker at Fairford, Gloucs and of Sir John Barrow at Ulverston, Cumbria to the monument to George Knowles at Sharow in Yorkshire, which echoes the style of the illustrated monument to Lady Louisa Bunbury at Great Barton, Suffolk.

The latter was for us the biggest surprise, as we had no idea it was there despite having driven past many times as it’s only ten miles from my wife’s village. This simple but rather elegant carving is signed T. MILNES, SC. at the base.

It wasn’t all plain sailing. In 1844 the Literary Gazette’s report on an exhibition at Westminster Hall [13] included: T. Milnes – The death of Harold at the battle of Hastings. This is the strangest collection of short trunks and consumptive legs ever congregated together. The same model (and that a bad one) must have sat for them all’. Perhaps unsurprisingly this sculpture is untraced! The writer didn’t confine his scathing remarks to Milnes’ work however, saying of Actaeon devoured by his hounds by R.G. Davies, ‘We wish the unfortunate hunter had been entirely devoured, so that we had been spared the sight of so disgusting a group’.

Despite this panning by the Literary Gazette, Milnes’ star was certainly in the ascendancy. In 1847 came the full length statue of Lord Nelson, now in Cathedral Close in Norwich, which was followed in 1848 by a statue of the Duke of Wellington. The latter was originally displayed prominently on Tower Green by the Tower of London [14] but in 1863 it was removed to the Royal Arsenal and is now in Wellington Park, Woolwich. A design for a funerary monument for Lord George Bentinck was exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851 [8].

Our favourite trip was to Saltaire, the Yorkshire mill town founded by Sir Titus Salt and now a World Heritage Site. In 1858 Milnes was invited to model the lions to surround Nelson’s column but it was not to be. The Bradford Observer [15] later pulled no punches in stating that through the influence, it is said, of a certain exalted personage, the commission was taken out of his hands and given to Sir Edwin Landseer. There was much public criticism of Landseer over his slow progress and indeed it was only in 1866 that the first of his four almost identical lions, cast in bronze, was completed. They were finally placed in position in 1867 [16].

A bust of Sir Titus Salt in Carrara marble, executed by Milnes and presented to Sir Titus by his workforce in 1856 [17], [18] , can be seen in Saltaire United Reformed Church. At some point Sir Titus became aware of Milnes’ models for the Trafalgar Square lions and it was London’s loss and Saltaire’s gain that he decided to commission sculptures based on the models and to place them in Victoria Road in the town. The Building News [19] related on 2 Oct 1869 that the first two had just arrived.

These magnificent lions, each weighing three tons and all different, were executed in Pateley Bridge stone. ‘Vigilance’ and ‘Determination’ stand in front of the Factory School while ‘War’ and ‘Peace’ (illustrated) are opposite in front of Victoria Hall. Superb detail is again displayed in the tympana, also by Milnes, on both of these buildings [20], [21].

Medallion portrait of a woman, clearly signed T. MILNES SC. at the base of the neck.

Image courtesy, Chris Bell