| The worsted textile trade in Bradford, and the story of Saltaire

Saltaire, located in England on the outskirts of Bradford, West Yorkshire is named after Sir Titus Salt. It was a purpose built village to house workers for his new textile mill, by the side of the River Aire and still exists today, perhaps the finest example of Italianate architecture in England. In December 2001, Saltaire was designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. This status is due to the dedicated work of local historian, Clive Woods and members of the local community. Today, Salt’s Mill houses the art work of David Hockney, a Bradford born artist, and sells an interesting and eclectic collection of books, furniture, jewellery, clothing, home effects and good food.

This is the story of how Saltaire happened...

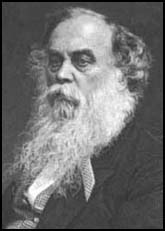

The worsted textile trade in Bradford started in the mid 1700s which brought people from the countryside and smaller towns, desperate for work. Textile workers, including small children, lived and worked in appalling conditions. There was little to no sanitation, the wages were pitiful and their labour was exploited which meant poor health and a very low life expectancy, around 18 to 20 years. At the beginning of the 1800s the population in Bradford was around 13,000. Titus Salt was born 20 September, 1803 into better circumstances. He was the first child of seven born to Daniel and Grace Salt, and when Titus was ten, the family moved to a farm in Wakefield, away from the health damaging smog surrounding the mills in Bradford. The family became members of the Horton Lane Chapel where Titus taught Sunday school. As a teenager, Titus was interested in health issues and wanted to train as a doctor but found that he couldn't cope with the sight of blood. His father encouraged him to learn the family wool stapling business, and at nineteen, moved with his family back to Bradford to concentrate on the booming textile industry.

The innovation of steam power was good for mill owners, increasing productivity and profit, but had a terrible knock-on effect for the workers as power looms made their skills redundant. Desperate to survive and ground down by terrible poverty, workers attacked the power looms in a bid to save their jobs. The authorities responded harshly, calling in the military. During such a confrontation at Horsfall Mills, Titus tried reasoning with the crowd but things were out of control - two workers were shot dead and others wounded. Titus enlisted as a special constable on the side of law and order, undoubtedly with a growing understanding of the struggle faced by the workers fighting for their low-paid and miserable jobs.

It was recognised that there was need for reform to help workers, but Humanitarianism still had a long way to go. The attempts at reform made by the Whig government were blocked by the House of Lords. In 1830, at the age of 27, Titus married Caroline. Life was going well for Titus and it was a time of boom for business, but always at the expense of the workers. Bradford's population had grown to over 43,000. Titus's father, Daniel, a church going man, was also of the opinion that reforms should take place and he offered his warehouse as a venue for meetings to discuss this, chairing the meetings himself. In 1833 Daniel Salt retired and passed the responsibility of running the family company to Titus. At this time, some reforms were passed by government. One such reform stated that children between the ages of 9 and 12 should not work more than 48 hours per week or nine hours per day. However working conditions remained harsh as children were still expected to work seven days a week. The living and working conditions of the workers were still terrible – pollution from the mills shrouded Bradford with choking smog, sanitation was appalling, infant mortality was high and life expectancy remained low.

In 1833, Titus spotted a consignment of Alpaca wool stored in a Liverpool warehouse. No one else was interested in it but Titus thought it was worth experimenting on. Alpaca was very difficult to weave but his persistence paid off and he found the wool could be transformed into the finest cloth if woven on a cotton or silk warp. This was innovative and was the key to his lasting success and immense wealth as a textile magnate. By the late 1840's Titus had five separate mills, was very rich, and had the means to improve the lives of his workers who were still living in sickening conditions. A social and humanitarian conscience was emerging in a wider sense - in 1844 Benjamin Disraeli published Coningsby, a novel about a factory owner who improved the lives of his workers by building them a church and a school. The following year, Disraeli published another book which described a purpose built village built for workers in Bingley, near Bradford by William Bushfield Ferrand, which greatly improved their living conditions.

In 1848 Titus Salt became Mayor of Bradford and started to work for the greater good in earnest. The Bradford textile industry and Titus Salt were on the up and up. Charles Dickens even penned an article called “the Great Yorkshire Llama” a playful reference to Titus Salt and his famous use of Alpaca wool. Titus made moves to eliminate smoke pollution and took his workers to Malham, a Yorkshire beauty spot, on a works outing, which was a significant gesture and a sign of his developing paternalism. |

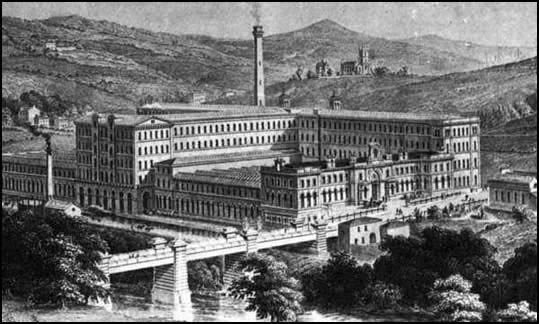

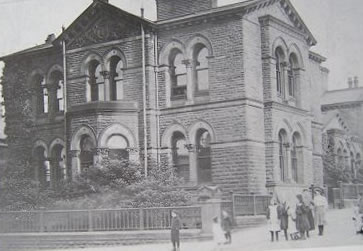

The new mill was opened on 20 September 1853, Titus Salt’s fiftieth birthday which was celebrated with a banquet for his workers in the mill’s combing shed. The mill was a masterpiece of its time and was hugely productive, turning out 18 miles of worsted cloth a day on 1200 looms attended to by 3000 workers. Over the next 20 years, Titus Salt’s vision became reality. Maintaining a rural setting, houses were built for his workers, each with a supply of fresh water, sanitation and a gas supply. The community became self sufficient with its own shops, hospital, school, library, park and church. There were alms houses for the poor and elderly, public baths and wash houses. Titus Salt’s paternalism forbade unions and public houses but, in general, workers’ lives had improved immeasurably. Along with introducing reduced pollution in his mills, and other health and safety features for his workers, he was the first employer in Bradford to institute the ten hour working day. Titus was created a baronet by Queen Victoria in 1869 which gave him the title of Sir.

The new mill was opened on 20 September 1853, Titus Salt’s fiftieth birthday which was celebrated with a banquet for his workers in the mill’s combing shed. The mill was a masterpiece of its time and was hugely productive, turning out 18 miles of worsted cloth a day on 1200 looms attended to by 3000 workers. Over the next 20 years, Titus Salt’s vision became reality. Maintaining a rural setting, houses were built for his workers, each with a supply of fresh water, sanitation and a gas supply. The community became self sufficient with its own shops, hospital, school, library, park and church. There were alms houses for the poor and elderly, public baths and wash houses. Titus Salt’s paternalism forbade unions and public houses but, in general, workers’ lives had improved immeasurably. Along with introducing reduced pollution in his mills, and other health and safety features for his workers, he was the first employer in Bradford to institute the ten hour working day. Titus was created a baronet by Queen Victoria in 1869 which gave him the title of Sir.